A short story in Vietnamese by Nguyễn Văn Thiện

Translator: Nguyễn Thị Phương Trâm

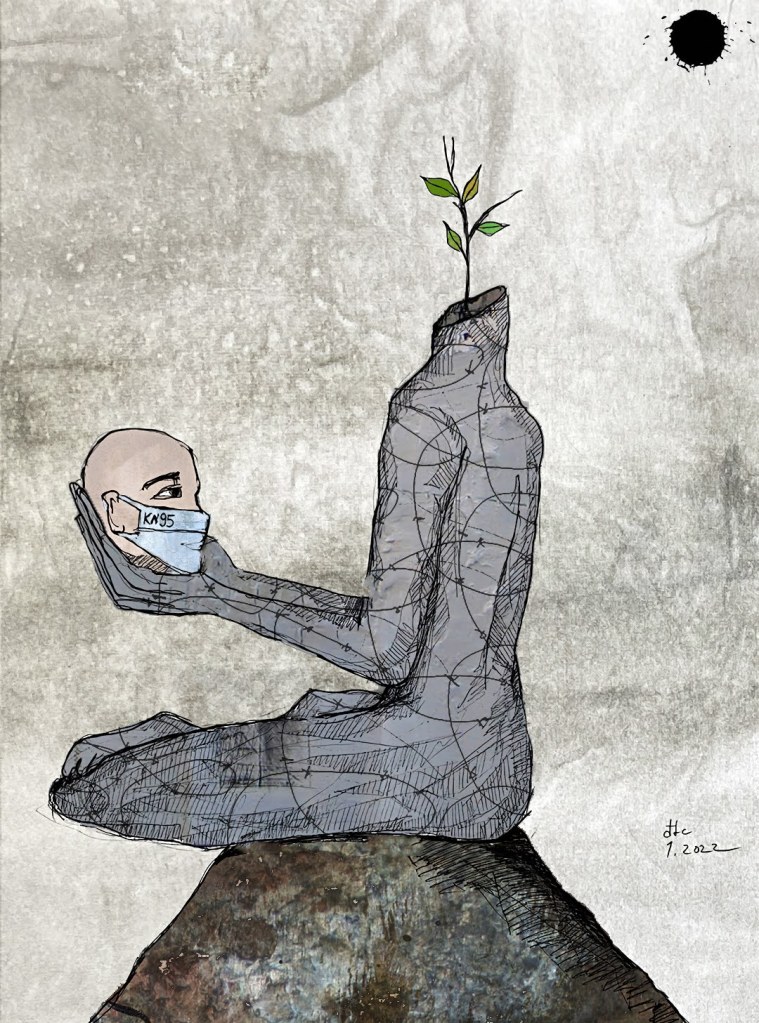

You’re cracking, I’m also cracking open, slowly every day, every hour, did you know that? A completed million-dollar highway, a metre thick, full of gravel and cement, but already cracking after one night. Let alone you and me, flesh and bone, fragile, full of dangerous openings, how would we not crack open?

I’m slowly cracking open, like flowers of the Queen of the Night, gently, virginal purity, miracle, if you don’t take note, you will miss its blossoming. This morning, on a familiar seat at a corner cafe, a ray of light by chance fell on me, like some wild lashing. Clearly showing up the cracks on my body, an odorous scar…

Long ago, when I was born, curled up in the hay on a December day, like a mouse, red and slimy. My mother often recalled: Your skin was really soft, like velvet. Your body was slippery like a watermelon! But the older I got, the more warped I became, and more dangerous, that is the pathetic cracks grew wider and wider.

I began to change after discovering the cracks on my body, like an autistic child. A poor student in a class full of well-to-do families, I sat quietly glancing from the mended stitches on my shirt to my friend’s uniform, head lowered, stared at my desk, tried to cover them up, but it was impossible. The cracks day after day grew bigger, they had a strange smell, how could I hide something like that! The patch of sunlight innocently aimed directly at them, like some awful joke of nature, they glistened…

I would wander in the grounds of the temple’s on my free days, collecting fallen leaves and piling them on the grass, I’m not sure why. Sometimes, a monk would pass by, chatting cheerfully, laughing. I was curious why they laugh at all, there’s nothing fun about being a monk. Their laughter crisp like pebbles splitting open at the bottom of a well, resounding, and a little creepy. After passing by, I sneaked a look at them from behind. Surprisingly, there was a long crack the length of the monks’ back, steeped in blood! It seems the monks were unaware of the cracks on their backs, if they had known, perhaps, they wouldn’t be laughing at all. I called out: “Reverend sir, your backs are also…”. But the monks didn’t hear me, the monks and their laughter disappeared forever down the dark long corridor of the temple. Leaving behind a metallic stench of blood, from the cracks, the smell overwhelmed the temple’s courtyard, like incense smoke during a commemoration…

Only my mother was aware of my crack. My mother was always the first to discover my wounds. My mother announced: “I’ll go up the mountain and pick herbs for the wound, about a month and it will be fine!”. My mother is a farmer, she has never stepped foot into a classroom, how was she so sure? She assured me, there are plenty of illiterate people who were medicine men! She would wait till I’m asleep, and chewed these leaves to cover up all the cracks. I would be dead asleep, the herbs were potent, I had nightmares from them, there was a knife made of fire, it was cutting my flesh open, like the wind from Laos long ago turning up while I was ox herding on sunny afternoons…

My mother never gave up, she wanted to cure me. But, for all my mother’s effort, the cracks changed from red to green, they smelt like steamed sticky rice. I would always add an extra layer of clothes, I tried to ease the chafing with what I had to survive, I worked hard and played hard. The cracks turned into an internal eye, always anxious, always watching.

The third eye could see the entire crack, in all the various crevices. At school every Monday morning for the National anthem, in the middle of the song when everyone was concentrating on singing, I saw our language professor’s chest cracked into halves, as though it was sliced open with a knife. And of course, he was not aware of the crack. His lips were still mumbling something as his eyes soberly followed the rising flag…

During the entire class, I couldn’t concentrate on a single word. The professor was discussing one poem or another, he complemented its rhymes, and absorbed power. He spoke passionately, now and then would place a hand on his chest, as though he was also in pain, hurting but couldn’t admit it aloud, worried his students might laugh at him.

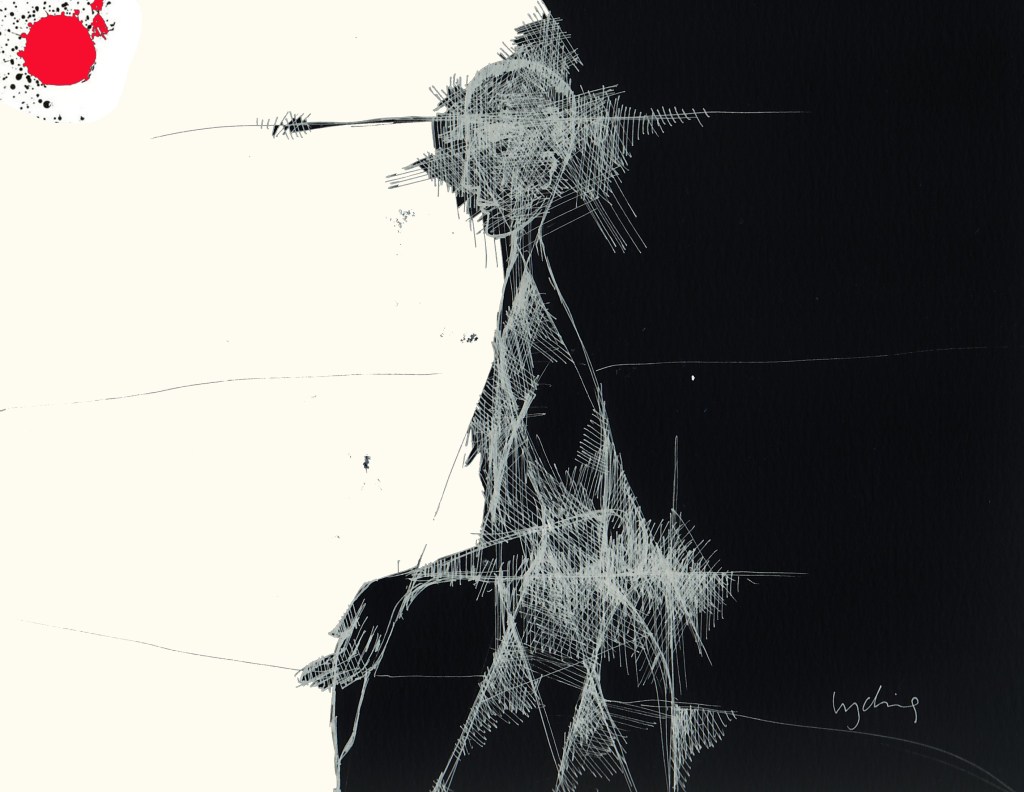

I left the class, went wandering. That night, I slept on the side of the road, beneath a bridge, with a bunch of homeless kids. I told them about the cracks, they all laughed at me. One of them said: “I saw, on my mother’s body, a huge crack, as black as anything”. I knew they didn’t believe me, they were teasing me. I left them, went home. In the middle of the night, the golden glorious autumn moon was glowing like an ode over my shoulders. I looked up at the Moon and it too was cracked wide open…

I have always loved the Moon, even through the craziest nightmares, but I’ve never seen a crack in it, now… Can you imagine a day without the Moon, what’s going to happen? I closed my eyes, curled up by the side of the road, homeless in the dark of night. And slept through the exhaustion, disappointment, and worries of what to come.

I woke up and the Moon was gone. The leaves rustling above my head, my hair was damp with dew. The Sun was rising.

I was very afraid to look at anything, putting on another layer of clothes, to cover up my cracks, cover my eyes, cover…

But how would one hide from the Sun, you can do nothing but look directly at it. If you look long enough, you could go blind. The green eye from the cracks stared at the Sun. It turns out, the Sun, not sure when, also has been cracked wide open. Lava leaked and oozed out of the cracks, engulfing the floating pink clouds, also already cracked wide open, for a long time now maybe…

You may ask me: “How come anywhere you look, you see cracks!”. I don’t have an answer for you, like a child who is asked a difficult question by a teacher, I would lower my head and live with the fault. The truth is, that’s not something I want. I want to be whole, the Moon should be full, the Sun should be a light over all things. But still, these were just my dreams. A student busy staring at his feet to avoid the stern glare of his teacher, terrified as he faced another fact, the ground beneath his feet was also cracking wide open…

When the ground beneath your feet is cracking wide open, where can you hide? No, there’s nowhere. I was like a fish out of water, drowning, fidgeting, every was out of focus. Long ago, you crawled out from a crack, hence now, you’re afraid, dare not to face it one more time? That was how I had encouraged myself. Lifting my head, holding my chin high, I was a samurai ready for harakiri, planted my feet firmly on the ground, I was ready and prepared to enter the wide crack opening up in the ground.

It turned out, the earth within, was no longer whole, there were so many cracks the length and width of the core, like gaping mouths, like scars, like ridiculous gaping wounds that won’t heal. And all this time, I thought the earth, this life, was solid and whole! In amongst wide open crumbling cracks were love, anger, disgust. I began my journey.

Long ago, I crawled out from a crack, and that is a fact!

_____

May 2020

VẾT NỨT

Bạn đang nứt toác ra, tôi cũng đang nứt toác ra, từng ngày, từng giờ, bạn có biết không? Một con đường ngàn tỉ đồng vừa làm xong, dày cỡ nửa mét, toàn đá với xi măng, mà chỉ sau một đêm đã nứt. Huống gì là bạn với tôi, bằng thịt bằng xương, mong manh, đầy những khe hở hiểm ác, làm sao lại không nứt được?.

Tôi từ từ nứt ra, như một bông hoa quỳnh đang nở, nhẹ lắm, tinh tế lắm, vi diệu lắm, nếu không để ý, bạn sẽ không thấy được đâu. Sáng nay, trên chiếc ghế quen thuộc ở quán cà phê cóc ven đường, một tia nắng vô tình chiếu thẳng vào tôi, như một làn roi man dại. Tôi nhìn rõ ràng khe nứt của mình, ngời ngợi, thơm tho như một vết thương…

Ngày xưa, vừa mới sinh ra, tôi nằm cuộn tròn trong ổ rơm tháng Chạp, như một chú chuột con, đỏ hỏn. Mẹ vẫn thường hay kể: Da mày mịn lắm, như nhung. Người trơn tru như một quả dưa hấu! Vậy mà càng lớn lên, tôi càng méo mó dần đi, và nguy hiểm hơn, là nứt toác ra một cách thảm hại.

Kể từ khi phát hiện ra vết nứt trên cơ thể mình, tôi trở nên khác tính, như một đứa trẻ tự kỉ. Một cậu học sinh nhà nghèo trong một lớp học toàn con nhà khá giả, cậu ta tự ngó vào mảnh vá trên thân áo mình, rồi lại nhìn sang quần là áo lượt của các bạn, và ngồi im lặng, cúi gằm mặt xuống bàn, cô giáo hỏi gì cũng không nói. Tôi đấy. Thỉnh thoảng tôi đặt bàn tay nhỏ nhắn lên vết nứt của mình, thử che lại, đậy lại, bịt lại, nhưng không được. Vết nứt ngày càng rộng ra, lại bốc lên một mùi hương quái dị, làm sao mà che nổi! Vệt nắng lại hồn nhiên rọi thẳng vào, như một câu đùa hồn nhiên đau đớn, long lanh…

Những ngày rảnh, tôi lang thang sân chùa, nhặt lá rơi rồi xếp lại trên cỏ, lẩn thẩn không biết là để làm gì. Thỉnh thoảng, có sư đi qua, nói cười hớn hở. Tôi băn khoăn không biết, làm sư thì có gì vui mà sư cười giòn đến thế. Tiếng cười như đá vỡ đáy giếng, vang vang, rờn rợn. Khi sư bước qua, tôi lén nhìn trộm từ phía sau. Thật kinh ngạc, lưng sư cũng nứt toác ra một vệt dài, đẫm máu! Hình như là sư không biết lưng mình bị nứt, nếu biết, có lẽ, sư sẽ không còn cười vui được nữa. Tôi gọi: “Sư ơi, lưng sư cũng…”. Nhưng sư không nghe thấy, cả sư và tiếng cười mất hút trong dãy hành lang nhà chùa tăm tối. Chỉ còn phảng phất mùi tanh của máu, từ vết nứt ấy, tỏa khắp sân chùa, như khói hương ngày đại lễ…

Vết nứt của tôi, chỉ có mẹ biết thôi. Mẹ bao giờ cũng là người đầu tiên phát hiện ra vết thương của con mình. Mẹ nói: “Để mẹ lên núi hái lá thuốc đắp vào, chừng một tháng sau thì khỏi!”. Mẹ là nông dân, không đến trường ngày nào, sao mẹ dám chắc chắn thế? Mẹ nói, đầy người không biết chữ cũng làm thầy thuốc, lương y đó con! Rồi lừa lúc tôi ngủ, mẹ lấy lá gì đó nhai đắp vào vết nứt. Tôi ngủ mê man, hình như lá thuốc công phạt khá mạnh, nên tôi mơ thấy có lưỡi dao bằng lửa cứa vào da thịt, như ngọn gió Lào ngày còn thơ dại dong trâu về giữa đồng trưa đầy nắng…

Bằng tất cả khả năng của mình, mẹ định chữa cho tôi hết bệnh. Nhưng, bù lại nỗ lực của mẹ, vết nứt chuyển từ màu hồng sang màu xanh lá cây, phảng phất mùi hương cơm nếp. Tôi khoác thêm một lần áo nữa, cho đỡ bỏng rát, rồi lại tiếp tục sống, tiếp tục vui đùa và làm việc. Vết nứt trở thành một con mắt bên trong, hàng ngày nhấp nháy nhìn ra, thao thức.

Con mắt thứ ba ấy nhìn ra, lại nhìn thấy toàn vết nứt, ở những chỗ khác nhau. Khi tôi lên trường học, vào buổi chào cờ sáng thứ hai, giữa lúc cả trường đang nghiêm trang, tôi thấy ngực thầy giáo dạy văn bị nứt đôi, như vừa bị một nhát dao sắc lẹm. Tất nhiên, thầy không biết mình đã, đang bị nứt. Miệng thầy vẫn lẩm nhẩm gì đó trong khi mắt thầy nghiêm trang nhìn lên…

Suốt buổi học hôm đó, tôi không nạp được một chữ vào đầu. Thầy giảng về một bài thơ gì đó, thầy khen thơ rất là có vần, và thơ có sức mạnh siêu gì đó. Thầy nói say sưa, thỉnh thoảng lại đưa tay lên vuốt ngực, hình như thầy cũng đau, cũng xót mà không dám nói ra, sợ lũ học trò cười thì phải.

Tôi bỏ lớp, đi lang thang. Tối đến, tôi ngủ ngoài vỉa hè, dưới gầm cầu, với lũ trẻ bụi đời. Tôi kể chuyện nứt toác cho chúng nghe, chúng cười hô hố. Một đứa nói: “Tao cũng thấy rồi, trên người mẹ tao, nứt to lắm, đen thùi lùi”. Tôi biết bọn chúng không tin nên chế giễu tôi. Tôi bỏ chúng, đi về. Nửa đêm, trăng thu vành vạnh trên đầu, như một bài thơ. Mắt tôi ngước lên nhìn trăng và ngay lập tức phát hiện ra, trăng cũng đã bị nứt toác…

Xưa giờ, tôi vẫn yêu trăng lắm, ngay cả trong những giấc mơ kỳ quái nhất, cũng chưa bao giờ thấy trăng nứt, vậy mà… Bạn tưởng tượng được không, nếu một ngày không còn trăng nữa, thì sao? Tôi nhắm nghiền mắt lại, ngồi co ro bên đường, như một gã hành khất giữa đêm khuya. Và tôi ngủ luôn trong mệt mỏi, trong thất vọng, trong những dự cảm không lành về tương lai.

Khi tôi thức giấc thì vầng trăng đã không còn nữa. Lá xào xạc trên đầu, sương ướt nặng trĩu trên tóc. Rồi mặt trời lên.

Tôi sợ lắm, không dám nhìn mọi thứ, khoác thêm một tấm áo nữa, để che vết nứt, để che đôi mắt, để che…

Nhưng với mặt trời, làm sao che nổi, chỉ là không đủ thị lực để nhìn thẳng vào nó thôi. Nếu nhìn lâu, mắt bạn sẽ bị mù. Con mắt xanh màu lá cây lại nhìn trân trối vào mặt trời. Hóa ra, mặt trời, không biết bao giờ, cũng đã bị nứt toác. Từ vết nứt vĩ đại xa xăm ấy, nham thạch rỉ ra, vương vãi khắp không trung, như máu. Nham thạch tràn xuống, phủ kín những đám mây màu hồng cũng đã bị nứt toác từ lâu…

Bạn hỏi tôi: “Tại sao nhìn vào đâu cũng thấy nứt!”. Tôi sẽ không trả lời được, như cậu bé học trò gặp câu hỏi quá khó từ thầy giáo, tôi sẽ im lặng cúi đầu biết lỗi. Thực ra, tôi nào đâu muốn thế. Tôi muốn tôi là tôi tròn trịa, trăng là trăng viên mãn, mặt trời là mặt trời chắc chắn soi lên vạn vật. Thế nhưng, đó chỉ là ước mơ thôi. Cậu học trò ấy loay hoay nhìn xuống chân mình để tránh ánh mắt nghiêm khắc của thầy giáo, và cậu kinh hoàng nhận ra rằng, đất dưới chân cũng đang nứt toác…

Khi đất dưới chân nứt toác, bạn sẽ trốn vào đâu? Không, sẽ không còn chỗ nào nữa hết. Bây giờ, tôi như con cá nhìn đâu cũng thấy mắt lưới bủa vây. Ngày xưa, bạn từng chui ra từ một vết nứt, vậy tại sao bây giờ, bạn lại sợ hãi, không dám đối mặt với nó một lần nữa? Tôi tự động viên mình vậy đấy, và ngẩng cao đầu, thản nhiên như một samurai sắp sửa tự mổ bụng, dẫm chân lấy đà, bước thẳng vào vết nứt toác vừa xuất hiện trên mặt đất.

Hóa ra, trong lòng đất, cũng không hề lành lặn, bao nhiêu là vết nứt ngang, nứt dọc, như miệng, như sẹo, như vết thương không lành nham nhở. Vậy mà lâu nay tôi cứ tưởng, mặt đất này, cuộc sống này, vững chãi lắm, lành lặn lắm! Tôi bắt đầu hành trình của mình giữa những nứt toác dở dang vụn vặt đầy rẫy yêu thương và giận hờn, khinh ghét.

Ngày xưa, tôi cũng bắt đầu đi ra từ một vết nứt, thật đấy!

Nguyễn Văn Thiện

Born: 1975

Home town: Anh Sơn – Nghệ An

Master in Comparative Literature and Critical Theories

Currently a high school teacher, and a prolific writer.

Editor of Chư Yang Sin (Đắk Lắk) Art and Literary Journal.

—

Nguyễn Thị Phương Trâm, the blogger, poet, and translator, was born in 1971 in Phu Nhuan, Saigon, Vietnam. The pharmacist currently lives and works in Western Sydney, Australia.